Today, we talk about the internationalization of the Renminbi. This issue must be well understood because it is intrinsically linked to the trade war between China, the United States and the European Union, the latter not currently involved directly.

I use an article Masciandaro published on the Italian newspaper, IlSole24Ore, which rightly asks whether China is willing to give up both the control of capital flows and the control of the value of the RMB itself.

My answer, which has always aroused criticism, is a clear “no” for reasons that I explain below, commenting paragraph by paragraph the article of Masciandaro.

From Il Sole24Ore: China and markets: the unknown is called Yi (link)

Two unknown factors will influence the future relationships between China and the world markets: one is very clear and concerns commercial exchanges, everyone talks about it and is called protectionism.

The other is less obvious, more institutional in nature, it concerns more the financial exchanges and the role of the Chinese currency, and it is the appointment of the new Governor of the Chinese Central Bank (PBoC) Yi Gang. The latter has a weight that can become exponential because it is intertwined with the first. The question is: will China continue the long march to make its currency competitive with the dollar, in a scenario in which commercial policies seem to have entered a phase of great tension?

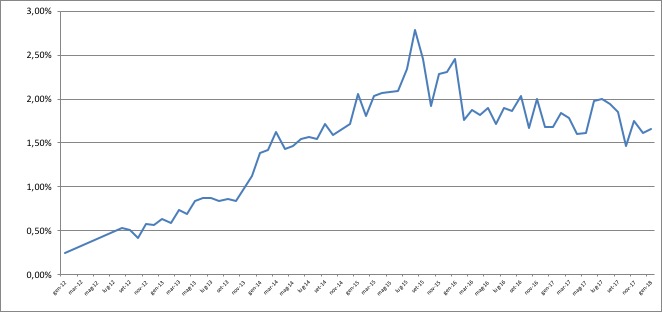

No. China not only will not continue its march but this march has already come to a halt in January 2016, when, as soon as the International Monetary Fund allowed the RMB to enter the SDR basket, the RMB began to lose importance as a currency used for International trade. In practice, before the IMF decision, the RMB had an upward trend that seemed unstoppable, continuing to step over positions as the currency used for international trade, surpassing the Canadian, Swiss and even the Japanese ones, and placed fourth in December 2015, preceded only by US Dollar, Euro and Pound. The use of the RMB, as a currency for international trade, had risen from 0.25% in January 2012 to 2.79% in August 2015, 10 times higher. At that moment, the Western assumptions on China were based on mistaken paradigms- extrapolating the past into the future without wondering why – the IMF on the basis of an optimistic forecast of the ever increasing weight of the RMB in the international arena, granted entry into the SDR basket, with decision taken on 30 November 2015, but with latest data available a couple of months before. But what has happened since? After reaching the “goal” of this international blessing, the RMB began to lose positions, returning to a lower value, and today it is used for 1.66% of transactions, back to the 2014 values. Thus, the IMF allowed entry into the SDR at exactly the peak moment! Coincidence?

The appointment of the new Governor takes place at a delicate moment in the international relations, in which the monetary trajectory that China has chosen over the past two decades can come into strong friction with what is happening in the arrangements of the international trade.

The PBoC is not an independent central bank, in the meaning that is attributed to the term in advanced economies. The PBoC is a central bank that is characterized by the dual mandate to pursue both economic growth and monetary stability – in this, it is identical to the Fed, the American Central Bank – but above all to be, in all respects, an instrument of the government in office, that is to say the Chinese Communist Party.

‘As it should be.’ To date, as recalled by Masciandaro, the Fed and the PBoC are the two central banks that have a double mandate for economic growth and inflation control, while the ECB must limit itself to controlling inflation. This makes the European economy compelled to compete between two giants, but without the possibility that the individual member states of the euro area, nor the ECB itself, can implement monetary policies aimed at the economic growth (the QE cannot be perpetual, and the bill of a long-lasting low-interest-rate monetary policy will come soon.)

As such, the PBoC has embarked on a long march in the field of monetary and financial policy, which can be summarized in a challenge: to make the Chinese currency – the renminbi – a so-called reserve currency for global trade.

The Chinese government actually has no intention of making the RMB an international currency. It is enough to have had the official recognition of the IMF, great media fanfare, but without having to bear the risks typical of countries that print reserve currency.

The beginning of the long run of the renminbi started in 2016 when the PBC published a report on the internationalization of the renminbi. But why has China set this goal? In general, for a country issuing a reserve currency can have three types of advantages. Firstly, there can be a commercial advantage in the strict sense, as the goods and services produced by the companies of that country – including banks – can benefit in terms of openness and penetration in foreign markets. Then, there is the monetary advantage represented by the so-called seigniorage: the more a currency is used, the more the State issuing it has net revenues that arise from the fact that normally the value of the goods that can be purchased with the issued currency is much greater of the costs of producing this currency. And finally – and perhaps above all – there are political advantages that the issue of a reserve currency confers, in terms of world power status.

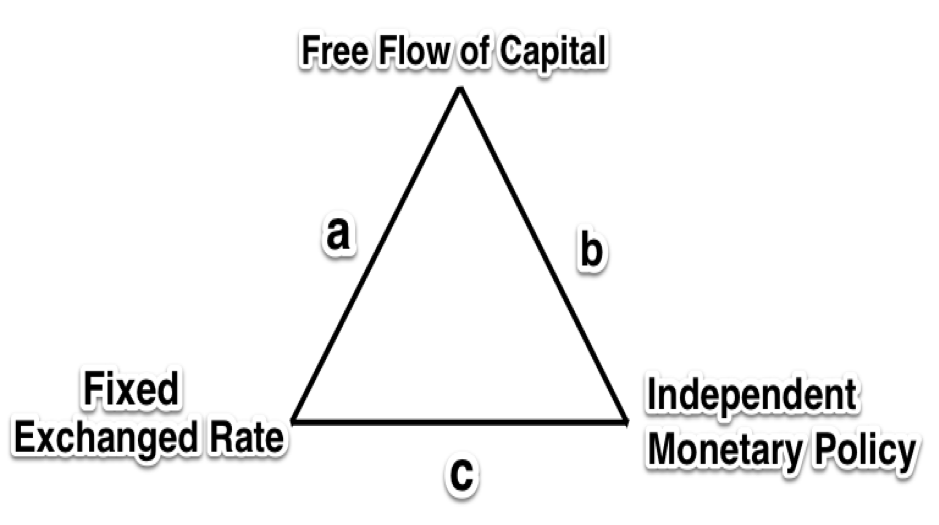

In reality, each of the three potential advantages has its downside, summarized in two constraints: not being able to control the exchange rate; cannot impose capital controls. It is these two constraints that can explain why China’s long march towards an international renminbi has been anything but linear.

The constraints can be summarized in the famous Impossible Trinity. In order to have a real reserve currency, China must necessarily open the capital account, since it can never renounce an independent monetary policy, as it should be. Open the capital account, therefore, means, open forever for any amount and at any time. But to do this, it must cede the power to set the exchange rate RMB / Dollar. Something that China will never do. It will never give up the control of the exchange rate to Wall Street, because this would imply imbalances not only on the value of the exchange itself but much more important, in the domestic interest rates. If China internationalises the RMB, it would give Wall Street the power of how to draw the curve of rates, a curve that I call “the mother of all the curves”, because it is from this curve that all assets are priced and is at the base of the economic stability of a country. Do we believe that China can pass on to the first Gordon Gekko, the control of its domestic interest rates, and the rates that Bank of China charges China Telecom when lending money? ” Good answer.

But today how influential is the renminbi? The answer is very difficult, especially on the empirical level. Using a recent indicator that measures the degree of influence of different reserve currencies on world GDP in the period 2011-2015 produces two results; from the qualitative point of view, the renminbi has a sphere of influence geographically limited to the area of Asia; from a quantitative point of view, as the Asian growth in recent years has been remarkable, the renminbi appears to be a significant reserve currency, given that its influence on the world GDP is 30%, exceeded only by that of the dollar (40% ), but higher than the euro (20%), not to mention the pound sterling (3%) and the yen (5%). Data to be used with caution, but that make us think. The renminbi’s march is still long, but it is not in its infancy.

What will Yi Gang do, by executing the Chinese government’s strategy? To continue the long march means to continue a path that foresees an ever stronger international integration of the Chinese banking and financial system. But the ultimate consequence should be the abandonment – credibly irreversible – of the weapon of controls of capital movements. In recent years, the Chinese financial system has taken on a physiognomy that resembles that of the American system before the collapse of Lehman Brothers: large, complex, opaque. A potential bubble that the Chinese government is trying to deflate thanks to capital controls. Can China afford to give up on them? And furthermore: integration implies the adoption – even this credibly stable – of a flexible exchange system. Is this also likely? But above all: how the continuation of the long run of the renminbi is reconciled – that is, the renunciation of two weapons of economic policy such as that of financial controls and exchange – at a time when the tensions on the side of the so-called protectionist wars would seem to push in the opposite direction? Great is the macroeconomic uncertainty under the sky, perhaps the Great Helmsman would say. He would be right

In fact, it is not compatible.